More power to decide what happens to your estate. That, in a nutshell, will be the result of Switzerland’s move to revise its inheritance law, parts of which (certain Civil Code provisions) have stood for almost a century. Given the way society has changed, an update was clearly due.

It has been a long process, however; the “Gutzwiller” motion to modernise inheritance law was submitted to the Swiss parliament back in 2010. The houses of the Federal Assembly finally passed the legislative changes on 18 December 2020 (information in French). As no referendum has been held concerning the new provisions, the Federal Council has decided that they will come into force on 1 January 2023 (information in French).

In this newsletter, we will bring you an overview of the main changes and their consequences for inheritance planning.

Descendants’ protected shares reduced and parents’ protected shares abolished

The central idea of the new inheritance law is to increase the testator’s freedom to decide what happens to their estate. Accordingly, the cornerstone of the reform is a reduction in the children’s protected share, and the abolition of the parents’ protected share (the so-called “forced heirship rights”).

As you know, the protected share, a civil law concept, is a set proportion of the legal share of the estate that cannot be withheld from certain heirs.

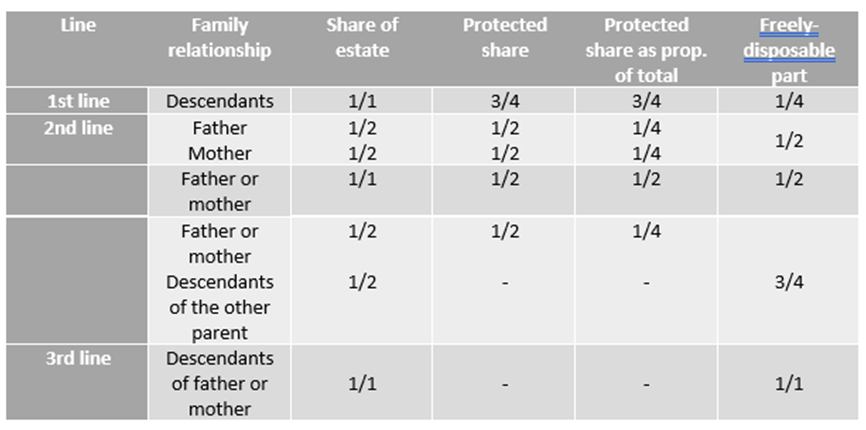

Overview of the current Swiss inheritance system

The Swiss Civil Code defines the statutory heirs in a succession, and the shares they are entitled to inherit. So, if the deceased has not left any testamentary provisions (for example a will), the statutory heirs inherit the estate in a certain order based on how closely related they were to the deceased (their line).

The closest line inherits, excluding the more distant lines. Consequently, the statutory heirs are always those in the closest line.

The first line consists of the deceased’s direct descendants: their children, whether biological or adopted, or the descendants of these children. The children inherit an equal share for each branch.

The second line inherits if no members remain in the first line. The second line includes the deceased’s father and mother, or if they are already deceased, the deceased’s brothers and sisters, or their descendants if any of them are already deceased.

The last line consists of the deceased’s grandparents and their descendants. This includes uncles, aunts and cousins, and their descendants.

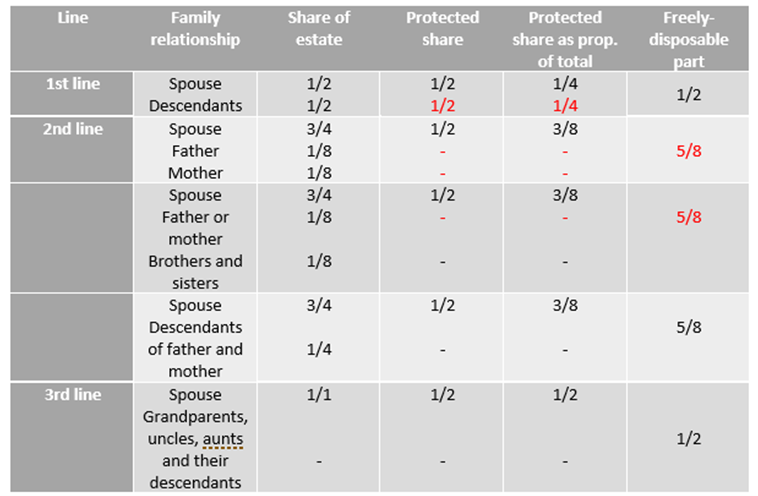

As the deceased’s spouse is not a blood relative, they are not part of the line of inheritance system, and their share of the estate depends on how closely related to the deceased the other heirs are.

So, in a family with two children, the spouse will inherit half of the estate, and each child one quarter.

If the couple did not have any children, the parents will inherit one quarter of the estate and the spouse three quarters.

In all other cases, the spouse will inherit the full estate.

Of course, people have the option to change the way their estate is divided and allocate a greater or lesser share to one statutory heir rather than another, or choose to leave their assets to a third party. However, as we said above, certain close relatives have an automatic right to a minimum share of the estate. Currently, under Swiss inheritance law, the following heirs are protected:

- surviving spouse,

- descendants,

- parents.

The protected share is:

- for the surviving spouse, half of their share,

- for a descendant, three quarters of their share,

- for the father or mother, half of their share.

The balance, which the testator can allocate as they see fit, is called the freely disposable part.

These rules are summarised in the tables below:

If the deceased was married

If the deceased was not married

It is also important to note that if the deceased was married, the marriage regime takes precedence over inheritance law. In other words, the marriage regime must be wound up before shares are allocated to the heirs.

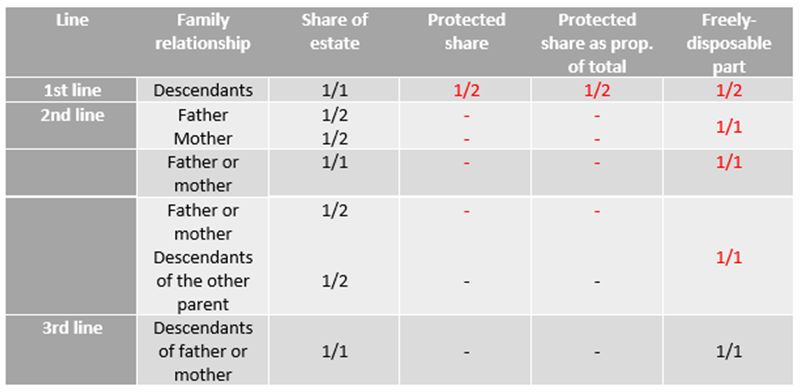

New inheritance rules

In the future, the protected share will be reduced to a half for the descendants, and it will be completely abolished for the parents. The spouse’s protected share will remain unchanged. This will increase the freely disposable part of the estate, as shown below:

If the deceased was married

If the deceased was not married

As the tables above show, under the new Swiss inheritance law it will theoretically be possible for people to freely dispose of at least half of their estate. They will have more options in terms of inheritance planning, to leave a greater share of their assets to one of their heirs, their partner, their spouse’s children or any other third party. In particular, these changes will make the process of transferring control of a business easier.

As indicated, the new provisions will apply to all inheritance procedures beginning on or after 1 January 2023. They will also cover pre-existing wills and succession pacts. So if you have already completed the estate planning process you will need to re-examine your situation and your intentions in the light of the new law, to make sure you make best use of all the freedoms it offers you. It is also important to clarify any ambiguity. If, for example, a will written in 2019 states that the descendants’ share is to be reduced to the protected share, it is important to clarify whether they should keep three quarters of their share or only half of it once the new law comes into force. The same question arises as to whether the parents keep their protected share or not after 1 January 2023.

Other changes under Swiss inheritance law

Spouses will lose their protected share and advantages once divorce proceedings begin

Another noteworthy change introduced by this revision is that the spouse’s protected share and advantages will be lost once divorce proceedings begin.

Under current inheritance law, if one spouse dies before the divorce is granted, the surviving spouse retains an entitlement to their share and their protected share in the estate. But the divorce process can of course last several years.

In the future, once divorce proceedings are initiated, the surviving spouse will lose their statutory entitlement to a minimum share so long as 1) divorce proceedings are brought or continued at the common request of both spouses, or 2) the spouses have been living separately for two years. The same principles apply by analogy if one of the partners dies during the process of dissolving a registered partnership.

It is important to note, however, that the spouse or registered partner’s right to a share in the estate will continue to stand until the divorce or dissolution order enters into force. In other words, to remove a spouse’s right to inherit entirely, an appropriate testamentary provision must be made. Simply bringing divorce proceedings is not sufficient to block a spouse’s rights under inheritance law.

In addition, any testamentary provision in favour of a spouse will only take precedence over other heirs if it is expressly protected by the testator. The same applies to wishes expressed in marriage contracts or property agreements, and logically to succession pacts.

Increase in the freely-disposable part when a usufruct is granted to a spouse or registered partner

When making a will, people frequently grant their spouse a usufruct for the entire share assigned to their joint children, who receive the bare ownership. The Swiss Civil Code (CC, art. 473) expressly allows this.

In this situation, the freely-disposable part is currently one quarter. Once the new provisions on successions come into force, this will increase to half of the estate. So, if the surviving spouse (or registered partner) has been treated as favourably as possible by the deceased spouse (in agreement with their descendants), they will be entitled to full ownership of half of the estate (as against one quarter under the current rules), corresponding to the freely-disposable part, and to a usufruct for the other half.

Clarification of treatment of the allocation of an additional share to a surviving spouse or registered partner by way of a marriage contract or property agreement

Under the current law, it is possible for a person to use a marriage contract to allocate to their surviving spouse all the assets acquired during the marriage.

As you will recall, under the standard marital property regime of participation in acquired property (CC, art. 196 and following), half of the value of the assets acquired by the deceased during the marriage is allocated to the surviving spouse when the regime is wound up (CC, art. 215.1). The other half forms part of the mass of the estate, together with the value of the deceased’s own property. However, a couple can use a marriage contract to make an exception to this rule and agree to divide the assets acquired differently (CC, art. 216). It is possible to allocate all the assets acquired to the surviving spouse when the first spouse dies. In this case, the estate of the first spouse to die is formed of their personal property alone.

There is however uncertainty as to whether this allocation is to be treated as a lifetime or mortis causa gift. This is far from being an academic question, because it has a direct impact on the base used to calculate the protected share and the order of abatement, as we will see further on.

The new succession law resolves this question by stating that a provision to allocate all the assets acquired during the marriage or partnership to the spouse or registered partner is to be treated as a lifetime gift.

However, in a departure from the bill drafted by the Federal Council (link in French), the Swiss parliament refused to agree to take account of the additional share of the assets acquired allocated when calculating the protected shares of the spouse and joint descendants. As is already the case under the current law, only children from other relationships and their descendants will be able to bring a claim in abatement regarding a marriage contract or property agreement (the protected shares will continue to be calculated based on two different calculation masses).

Treatment of individual linked protection assets within an estate

The inheritance law revision explicitly states that pillar 3a assets will continue to be excluded from the mass of the estate, for both the recognised forms of individual linked protection (bank or insurance company).

Pillar 3a claims are however incorporated into the mass of the estate for the calculation of protected shares (for the surrender value of a pillar 3a with an insurance company only; the proposal in the initial draft to include all life insurance claims was abandoned) and are consequently liable to abatement, regardless of the form of individual linked protection chosen. This means that heirs with a statutory entitlement who are not allocated their protected share could bring claims in abatement against the beneficiaries of pillar 3a for the sums lacking.

The inheritance law revision will not have any effect on pillar 2. Payments from occupational benefits plans, whether mandatory or non-mandatory, do not fall within the mass of the estate and are not liable to claims in abatement.

Clarifications regarding the order of abatement when the protected share has not been allocated

Under the law, an heir with a statutory entitlement who does not receive their protected share can demand (CC, art. 522 and following) the reduction of the deceased’s testamentary provisions and certain lifetime gifts made within the five years prior to their death, with the exception of customary gifts.

A degree of uncertainty does however remain as to the order of abatement, that is to say the decision as to which assets should be reduced first in the event of such a claim.

The new inheritance law brings welcome clarification by expressly stating that property which passes to heirs under intestate rules i.e. the proportion of the estate that an heir receives in application of article 481.2 of the Swiss Civil Code, or that is received independently of the intentions of the deceased can be abated. The new law states that first, the statutory heir’s share shall be reduced to the level of their protected share (in a so-called intestate succession). In a second step testamentary dispositions may be reduced and, finally, lifetime gifts.

Lifetime gifts are abated in the following order:

Firstly, gifts given by way of a marriage contract or property agreement, then freely revocable gifts and payments from individual linked protection and lastly other gifts, working back from the most recent to the most long-standing.

Ban on making donations after having signed a succession pact

As you know, a succession pact is a contract signed in front of a notary (as a public deed), between two or more people, regarding the succession of at least one of the people. It is the only legal instrument under Swiss law capable of overriding the protected share. The testator can therefore allocate their estate freely with no limits, so long as they have the agreement of their heirs.

This is a way, for example, for a child who has received money or a part of their inheritance during the testator’s lifetime to give up all or part of their entitlement to the estate. To be able to sign a succession pact, a person simply needs to be aged 18 or over and capable of judgement. Unlike a will, a succession pact cannot be altered unilaterally. Any change must be made in the presence of a notary and with the involvement of all the parties.

A succession pact can encroach on the protected shares of other heirs who are not signatories to the pact. Anyone whose rights have been encroached on in this way can bring a claim in abatement.

Under current case law, after signing a succession pact, and unless the pact states otherwise or there is a clear intention to cause harm, the testator is free to dispose of their property by making lifetime gifts as they wish. This will no longer be allowed once the new inheritance law enters into force, unless it is specifically provided for in the succession pact. It will therefore become possible to challenge testamentary provisions and lifetime gifts in excess of customary gifts if they are incompatible with the commitments made in a succession pact, unless provision has been made for them in the pact.

Conclusions on the new Swiss inheritance law

We can only welcome the reform to Swiss inheritance law. It will give testators more flexibility. They will be free to decide how they dispose of a greater proportion of their estate, with fewer limitations imposed by protected shares.

It is important to review your estate planning in the light of this reform, and to revise your will, in particular to clarify whether any reference to “reduction to an heir’s statutory share” made before 1 January 2023 should be interpreted under the old or the new version of the law. Similarly, it is important to clarify whether the testator has the right to freely dispose of their assets after signing a succession pact. Lastly, should you initiate proceedings to divorce or dissolve a registered partnership, making new testamentary provisions is crucial.

On the other hand, we sincerely regret the Swiss Parliament’s decision not to accept the proposal by the Federal Council (link in French) to establish a claim for maintenance in favour of life partners. The idea of this was that if the deceased lived as a couple with a life partner, this partner would, under certain conditions (in particular a minimum period of 5 years living together and the surviving partner being left with resources below subsistence level), have a claim on the deceased partner’s estate which could not be excluded in a will or agreement before death.

This change to inheritance law would have been in line with modern society: many couples decide not to marry or enter a registered partnership, but simply live together.

Alongside this revision to inheritance law, another set of measures is being brought in to make it easier to transfer control of family businesses (link in French). The Federal Council has proposed a number of legislative measures which were largely supported during the consultation process in 2019. They cover in particular the valuation of companies (taking into account the market value of the undertaking within the business assets at the time it is transferred during the person’s life rather than when the estate is wound up, to avoid later adjustments with other heirs), the right to allocate the business as a whole to one heir only on a judge’s decision and an option to postpone the compensatory payment to the co-heirs (for a maximum of 5 years). The Federal Council’s dispatch is due to be presented to Parliament before the end of the year, with the new legal provisions on transferring control of family businesses potentially coming into force on 1 January 2023.

We would also like to mention that an amendment to chapter 6 (in French) of the federal law on private international law regarding international successions is also under way. The aim of this revision is, as far as possible, to harmonise Swiss law with the European regulation on international successions and in particular to allow Swiss citizens holding dual nationality to choose to have their estate wound up under the law and jurisdiction of their other nationality.

*****

The contents of this newsletter are not to be construed as a legal or tax opinion or advice. Should you require more information, please either email us or get in touch with your usual contact at Croce & Associés SA.

This newsletter is available in French and English on our website www.croce-associes.ch.